From now on I was a prisoner of war and the new ordeal lasted another 2 1/2 years. At that moment, however, the war was over at least for me. A strong feeling of relief and joy flooded my mind and I had all reason to be thankful and glad. My uniform was tattered, alright, but my body remained wholesome and uninjured except for a wound in the back I had not even discovered yet. Our captors were Americans, and under the circumstances a very much appreciated luck.

We were lined up in front of a big and deep ditch. Are they going to kill us? One never knows. Instinctively, I slipped back into the last row. Whatever might happen, I had no desire to be the first to fall into that grave. Thank God, they searched us only for hidden weapons, then we marched out of the woods to the road from Falaise to Argentan. What I noticed there was surprising and utterly impressive. Mile-long columns of tanks, manned with fresh troops, were ready and waiting to finish the battle. Huge piles of ammunition were stored along the road. With bitterness, I remembered the words Hitler shouted angrily after the assassination attempt a month ago at midnight. “The leadership is great and provided everything, but the troops are cowards, not worthy of an ingenious leader.” This provocative speech was truly enraging. I was ready to kill that madman with bare hands. Not only were millions sacrificed on the altar of his megalomania, but more so, he topped his hypocrisy with insult and spat in the face of his soldiers who had to bear the brunt of his deranged fantasies. Almost empty-handed were we sent into the battle and now I was stunned by the sheer unlimited resources of world powers we had to fight for no other reason than to boost the ego of a pathological maniac.

We marched into the night and marched. The air was sticky. A thunderstorm broke loose after midnight unleashing heavy showers. It did not bother us. We opened our overalls to collect the precious water and drank it to quench our burning thirst. Before dawn, Argentan was reached and we were led into somebody’s backyard. The ground was soaked with rain water, but we were ordered to lay flat. Noticing a puddle under my feet, I hesitated and was roughed up. Go down or be shot. With the rising sun, a blue sky opened up warming slowly body and mood. C rations were distributed. The first food since days. Soon after the guards delivered us to a nearby camp, a field hastily fenced in with barbed wire. No tents. In the center was a stinking cistern surrounded by landsers who quarreled for a cup of foul water. On the other end, I saw a group assembling. Curious I went over. A number of trucks loaded prisoners to ship them, somewhere else. “What can be worse than this camp?” I reasoned and got in line. Pressed together on the open deck like herrings we proceeded to a new destination. In a curve, the driver swerved, ran into the ditch, and tumbled over on just the side I was standing. The whole pack fell upon me squeezing the last breath out of my lungs. Fortunately, the accident had no serious effect and soon we were on the road again. The new camp was not better equipped and so for a week, I passed through one camp after another.

Only one had good food and tents, all of them occupied. When rain started to fall late afternoon, I stood there on one leg like a stork and freezing. Why should I spend the entire night in such a miserable position? I ran to the gate and was hauled away swiftly as half a dozen times before. My good friend Guenther somehow had been separated from me and I really missed him.

Finally, I landed in Cherbourg, the famous Atlantic harbor. The compound had been erected on top of a high cliff overlooking the ocean. The salty breeze whiffed over the steep edge. It was a well-organized camp, divided into numerous sections. SS men and potential war criminals stuffed in one of them were under continuous investigation. I myself was lumped together with a large army bunch. But life seemed to become more tolerable. A choir was already formed and the songs could be heard throughout the whole area. Our neighbors, the Ukrainian Tartars, played on banjos and guitars. Their uninhibited laughter and gay folk songs instilled a new spirit in each of us. These unsophisticated people knew how to enjoy every minute of life and did not bother about what the coming day may have in store. The absence of psychological complexities made it easy for them to cheat and steal without scruples, and they were masters in that business. During the daily ritual of food distribution, they usually brought home a surplus box. After a while, the American commander took it seriously and closed the gate for 2 days. Imagine 2 days without food. We had no fat reserves to welcome such a measure. My stomach grumbled so loud on the second day I could not resist walking to the garbage pile and fishing out the last bits I was able to find. The Tartars had been straightened out. In retrospect, I can only think of these men with pity. After the war the Allied governments delivered them forcefully to the Russians, who by order of Stalin eliminated them, to use the Communistic term for cold-blooded murder.

The tents had not sufficient capacity to accommodate everyone. Thus we could squeeze only half of the body under the tent leaving the other half outside with two choices. Either get suffocated in the stink or drown in the rain. And let me tell you, the precipitation rate along the Atlantic is high. As you may expect, some of those guys under the same roof were dirty slobs and loaded with lice. It was natural, therefore, on the first sunny day to hang up our shirts at the barbed wire and search for bugs. My shirt did not come loose. Looking into a mirror I discovered to my surprise a long cut just half an inch from the spine. I showed the wound to the medic, but he was not impressed. “Don’t worry,” he said, “You are OK.” Well, the injury healed anyway. Not even a scar remained.

The lazy days in Cherbourg ended abruptly. I was pulled out; together with a small group, I boarded a truck that hauled us along the Atlantic coast. Idyllic fishing villages which we passed through excited my interest. We traveled through Granville and St. Malo before we took a turn toward a mountainous region. I enjoyed the trip. Annoying was only our black guard who with his finger on the trigger and the rifle aimed at our heads rocked up and down his seat while we rolled over bumpy roads. At least it made me uneasy. In one village a mob tried to stone us but retreated quickly when our guard leveled his gun against them. The French as a whole seems to be a vindictive nation. The Americans knew that. “We send you to a French camp,” was the most deterring threat. In fact, prisoners lucky to get out of French captivity told us horror stories. After the war, a big scandal arose when 400,000 German prisoners known to have been in French compounds were missing. At that time, however, the wave of hatred against Germany was excessively great, understandably, so that cruelties of this kind were quickly toned down.

“I became inspired to write a composition for violin and organ which, though modern, was premiered in the local Presbyterian church and received quite well by my co- prisoners.”

We stopped in a labor camp. There was good food and each one of us got half a tent. Since my uniform was in tatters, I received a new, heavy, dark blue overcoat which kept me warm during the coming frosty fall days. Every morning, we marched pretty far out to repair railways and bridges. In the evening, I crawled exhausted under the tent and removed the totally wetted shoes and socks. The next morning, they were still wet. I can’t remember that I ever had dry feet. We learned to fabricate gasoline lamps from empty vegetable tins and soon the whole camp was illuminated. Our life seemed to approach civilization. To feel still warmer and cozier we dug a foot-deep hole in the ground under the tent, snuggled in, and slept like hibernating bears. On Sunday afternoon a heavy thunderstorm dumped several inches of rain upon us. The water came shooting down the hill like a river overflooding our holes. For days we had the dubious pleasure of enjoying waterbeds. This lifestyle, not much different from that of a caveman, was of course not conducive to health. Like many others, I suffered from diarrhea and grew weaker and weaker. The only alternative to escape this animal-like life was to work less and be removed. Surely, it was a risk. Nevertheless, I had enough after 2 1/2 months and gambled. One day the truck waited outside to haul away the obstructive men. This time I was among them. To our surprise, they shipped us back to Cherbourg and I must say I was truly happy to see the familiar environment again. Unfortunately, the enthusiasm was short-lived. The coming morning, we marched to the harbor and boarded a ship. Not a luxury liner. No. It was one of those Kaiser ships supplying the front with war material. The rump of such a vessel is comparable to a superhall. Selecting carefully the pivotal point in order to minimize the effect of rolling and tossing on the high sea, I sat down and nibbled on the rest of the red beets and biscuits I still had in my pocket. Thus, I sustained the first ocean journey of my life without vomiting. But I tell you, it was hard to defeat the creeping urge, continually nourished by the stirring sight of guys running to the big barrel gurgling and spitting.

We landed in Southampton, Great Britain. A train waited to bring us to London where everybody was bathed and disinfected including our clothes, which retained a terrible smell long afterward. All items collected during the last 3 months were taken away. But I was lucky to retain my dear blue overcoat. Gone were also my friends from the labor camp. Sluiced through the cleaning procedure, I found myself among a new group ready to travel in the direction of northern England. While we waited at the train station a crowd gathered and stared at us as though we were exotic animals. As we walked to our reserved compartment some women followed and our guardsmen had a hard time keeping them out. Stern-looking as they were in public, they thawed up quickly once we were alone. To entertain them, we sang familiar German folk songs and they in turn sang their favorite English tunes. It was fun and the time passed quickly.

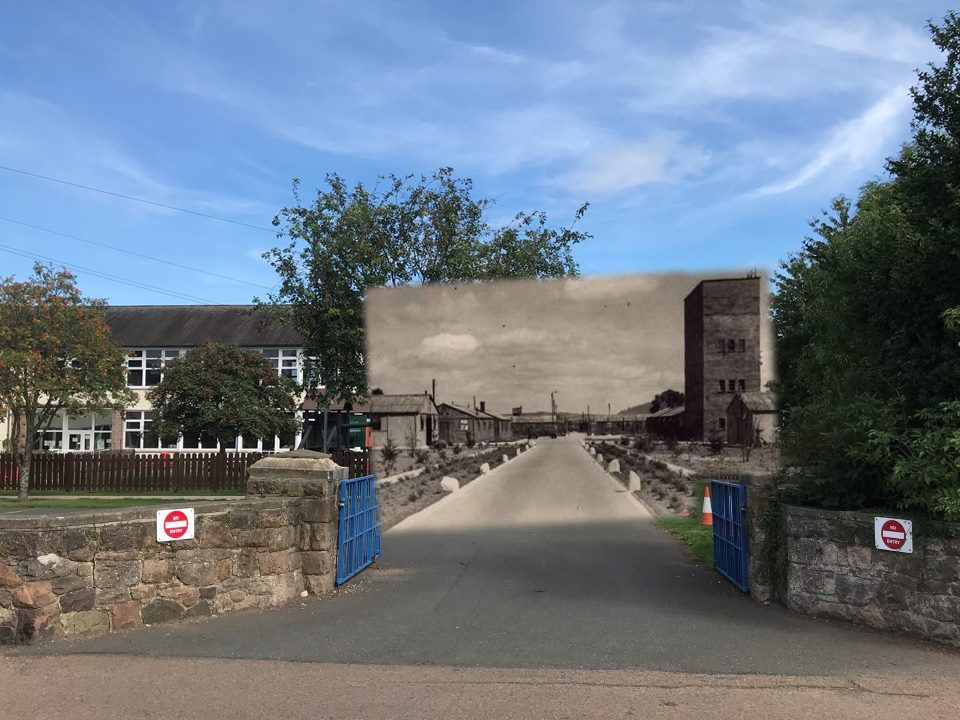

Near Coventry, we were released into a huge compound holding several thousand men. Somebody led us to the new quarter back in the woods, a so-called Nissenhut, which is actually a sheet metal tunnel on a concrete slab. The hut was empty. The temperatures approached the freezing level. After all, we had mid-November. How to spend the night under such circumstances? Man help yourself. We took our underwear off, filled them with dry leaves, and slept on them; not very comfortably, of course. As a transitional measure, it was alright until regular beds, straw mats, and even a stove were provided. The only problem left was how to heat without fuel. Well, we found ways to organize what we needed and a few weeks later we were all set. With a pickax we felled trees. Without a hammer we built a table and a coal box using what could be found laying around the camp: rusty nails, useless boards, and numberless items which people accustomed to boundless supply consider waste. But ingenuity creates everything if there is a real need. Once in a while I roamed through the neighboring huts and with great astonishment I noticed how skillfully some men produced the most fabulous toys like sorcerers. Their castles, chess games, dolls, and others, wonderfully carved, were put on display in showrooms just before Christmas. Even the English commander was amazed and thought it appropriate to distribute the entire collection among poor children.

There was plenty of time now every day. Most of the prisoners spent hours chatting, hiking, boxing, reading, you name it. But my mind was busy digesting the events of Normandy. Having faced death there so often shook me to the last fiber. Ideas sprang up from unknown sources and I decided to write them down in a poetic form, which was difficult without having paper and pencil. I strolled to the barbed wire, the trading place for almost everything, and induced a guardsman to procure it. He did it without even a charge. Within the next 3 months, 12 philosophical poems were born. It was an attempt to get off my chest what had bothered me for a long time. The phenomena of war, suffering and death, freedom, and spirituality, the odds of our very existence were molded into language. During that period of concentration, I stayed very often outside stepping through the woods and enjoying the stillness of nature. The weather too could be scarcely more gracious. Every morning the sun rose gloriously promising a warm sunny day. Half an hour later the glory disappeared, a veil of grey mist crept in and hung over the country till evening. The last 15 minutes prior to sunset the golden disc penetrated the fog pale faced, the last greeting before the clear night spread quietly over us with sparkling stars.

March 1945. For 4 1/2 months, I looked around critically and found out that the camp was mostly occupied by paratroopers, Hitler’s most fanatical followers, as well as former SS officials who still preached the old gospel of hatred and Germany’s final victory. Since we were so close to the end of the war, I assumed the harsh realities had some sobering effect on their distorted minds. Oh, no. The western front was already on the Rhine River and the Russians invaded already East Germany, but those guys fantasized about paratroopers coming down like angels to liberate us. Anyone having doubts was threatened. A farmer and father of 5 children, assuming he could speak freely, was strangled, and hung on a tree in the middle of the night. His life was saved only because a camp guard spotted him accidentally in time. The commander was furious and closed the gates. No food, nothing at all was admitted until the guilty ones were found. Three paratroopers under heavy pressure finally turned themselves in and were sentenced to 7 years of hard labor. Similar cases occurred commonly in other camps, where radicals outnumbered the moderates, and often [the disagreement] ended with murder. Just listening to their bragging of crimes and terror turned me off, and against my will, a deep aversion to Germany, in general, started rooting in my mind, which many years later became a decisive factor in our resolve to emigrate. I certainly was not the only one who was disgusted. Soon I met 13 other men of similar views. We drafted a petition to the commander asking to be transferred to a so-called anti-Nazi camp. Our wish was considered favorably and a week later 14 radicals, the exchange group, entered the campground. The news sped around like a whirlwind. People otherwise friendly acted suddenly defiant and did not hide their contempt. We were marked as traitors and our presence in the camp became increasingly dangerous. The commander moved us away quickly. Overnight we slept in the kitchen well guarded. As we stepped up to the truck early the next morning, hundreds gathered behind the fence shouting threats in helpless wrath. I became angry too and unleashed my tongue unbridled. These stubborn dumbheads, this mob incapable of straight thinking and blinded by an inhuman ideology have ruled Germany for too long already. I swore, whenever I will be back, this pest should be kept in abeyance.

By train, we traveled north in dense fog for hours. Some distance from the city of Leeds we rushed out of the milky soup and left behind a white wall. Two years later on the way home, we were swallowed by that wall again, which seemed to stay there forever. A strange phenomenon. Indeed, northern England remains usually free of mist. A heavy wind blowing consistently from the ocean shapes a climate very different from the rest of Great Britain.

Our destination was Wooler, a small town in Northumberland, not far from the Scottish border. Wooler spreads out in a green valley surrounded by even greener mountains not higher than 1000 feet, covered with tall ferns. No trees, no rocks. The sky was overcast pretty often. Came the sun through, however, the people rolled up their sleeves and enjoyed these rare moments. The Wooler camp was a labor camp occupied mostly by farmers and craftsmen who had enough of the war and dreamed just one dream: to go home. A few only were still clinging to Nazism but kept quiet because of the overwhelming anti-Hitler sentiments voiced in particular by former Socialists and Communists. Nevertheless, the atmosphere in general was tolerant and pleasing. A Catholic, as well as a Protestant priest, took care of the spiritual needs, which were not very obvious or pressing. A respectable choir under the baton of a professional organist, two accomplished violinists, and a quite good little theatre group entertained us over the weekends. The performances were on such a high level that I became inspired to write a composition for violin and organ which, though modern, was premiered in the local Presbyterian church and received quite well by my co-prisoners.

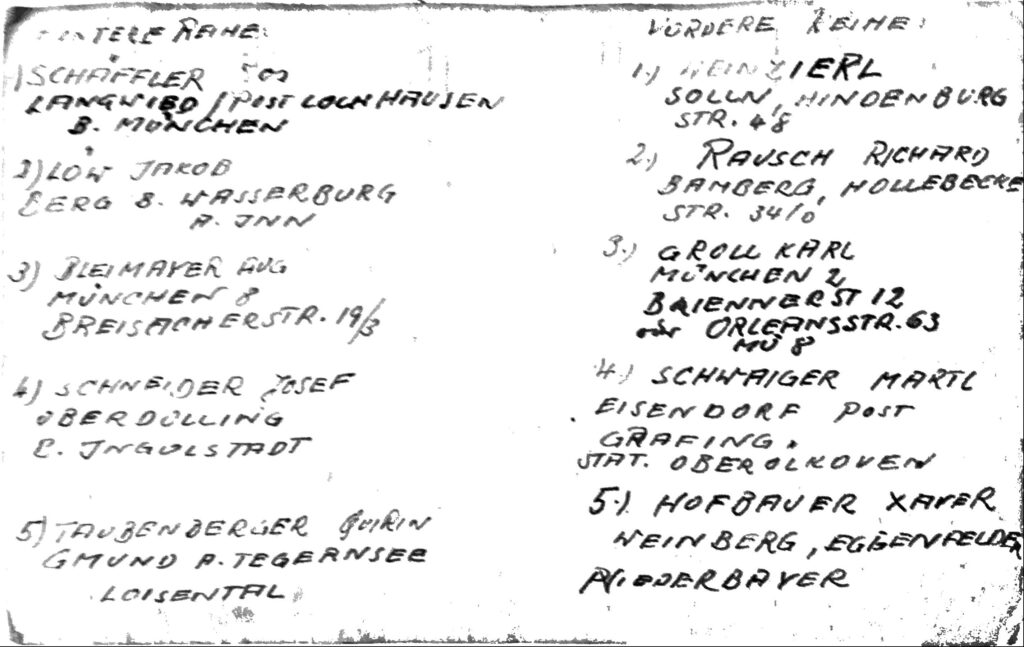

Throughout the summer of 1945, I had to work every day outside the camp cutting grass, hauling cow manure, digging ditches, and other laborious chores actually too strenuous for an untrained person like me. But I had no choice until I got clever enough to find out about the easy jobs available, which for a payment of one shilling per day were still sufficiently drudging. The money was not even handed out but instead credited to an account for a full year before we could draw it and buy some niceties like coffee, cake, cigarettes, et cetera. By that time I was fully established as an interpreter, news reporter, article writer, musician, and speaker, functions which made me eligible for office work. Together with Rudi Mai, a young student, I handled all the banking matters of some 1500 people. This was more to my liking and gave me a handle on dealing with the camp leader and especially the English political advisor, a former Austrian Jew who wielded quite a power over our fate.

In May 1945 the war ended. Germany suffered total defeat. What happened to our families? Were they alive? Under which conditions? We groped in the dark, our imagination fanned only by rumors, some strange and weird which consistently spread through the camp often tentatively set in motion for pure fun. Our men cut off from normal life for years were vexed by unfulfilled desires and genuine anxieties. The conversation chiefly spun around food and women often expressed in uninhibited language bordering on lasciviousness; the love stories narrated in colorful oriental style reached into minute details. So much I learned. Food and sex are the basic forces to drive mankind. A few only, very few grow above elementary instincts. I myself felt and suffered not less than my buddies. Some of them could not bear it any longer, became mentally deranged, and committed suicide, or simply walked away to go home. Even so, it was clear they would not go very far. The tense situation did not relax until the middle of 1946 when we got permission to write and receive letters. Around the same time, the camp gates opened for us also and we could freely roam during the weekend where we wanted to. In retrospect, I am much more appreciative of the English generosity than I was then. Indeed, it was a gorgeous and even risky gesture that enabled us to become acquainted with the countryside and lifestyle of the population.

Although Northumberland is located at the same latitude as Copenhagen, the air never felt too cold or particularly warm. In summer the daylight scarcely faded away. In winter I observed the most unusual colors and magic lights radiating from the sky and casting a spooky spell over the landscape. One phenomenon, in particular, was so unique and fantastic that I never forgot it. After an intensely sunny day in autumn, I made my daily walk at dawn around the camp. Looking up to the greenish purple sky, I saw an unusually bright spot shooting a green ray from one end on the horizon to the other end staying there like a long finger. A minute later another superlight appeared growing immensely and bursting into a thin ray as before. The spectacle repeated until the entire firmament hung full like a cobweb. Then the threads began breathing and wobbling faster and faster and finally melted together to one boiling mass of golden, purple lights swinging and dancing in great excitement. In awe and amazement, I stood overwhelmed until the grand apparition slowly died and vanished. What I had seen the scientists call aurora borealis, the northern light, which rarely paints the sky with such striking and unreal beauty.

A rumor whirled through the camp in the fall of 1946. The first group of prisoners will be released. My name was on the official list. Oh, joy beyond imagination! More than 3 1/2 years have passed since I had seen my dear ones the last time. Several days later the candidates were summoned for final instructions. I was not called. Fearing the worst, I went to the office and found my name scratched out by order of the political advisor. This was strange and I asked the camp leader for an explanation. “You cannot be substituted right now,” I was told and therefore I had to stay. But I had a hunch that the political advisor took his revenge for my repeated refusal to deliver the names of comrades he held in suspicion for minor misconduct. My hopes shattered, embittered and sad, I slowly returned to the barrack and wept. Four more months later my release was finally granted, but only after the advisor had been replaced.

“What do people know about freedom who never suffered confinement?”

We were only a group of four. Early in the morning, we left the camp unnoticed. In Hall, we boarded a sizable steamer with 500 other fellows. The journey was rough and except for 5 men, we all became seasick. These happy guys had a great feast on the breakfast table while the other 495 of us were more dead than alive. I tried to fight the awful feeling by all means. The warm, oily smell, however, and the horrible stench emanating from the emergency barrel constantly in use by coughing, moaning victims subdued at last my resistance. What a tormenting experience. The stomach convulsing vehemently, even when empty, was hurting so badly that one feels like dying slowly in exhaustion and agony. To my surprise, the torture was suddenly over in the midmorning without any after affects. Luckily, I escaped the cleanup operation. Just a short glimpse at the unbelievable mess was sickening. The ship anchored in Cuxhafen, the German harbor. A train waited to bring us to the former concentration camp in Dachau near Munich. Subzero temperatures froze our bones. The compartment windows were closed with cardboard. The heating system did not function for a long time. But we were on the way home and nothing could bother our gay mood. After 2 days the train stopped in Dachau. The barracks previously filled with thousands of hapless victims of the Hitler terror served now to channel the German prisoners of war back to civilian life. The American military checked mainly for SS men and war criminals. The rest received ration cards and a little bit of money. Quickly we were ushered away. As I stood outside the gate an odd feeling overwhelmed me. Did I not dream? Free? I was finally free? What do people know about freedom who never suffered confinement? They cannot appreciate the great gift that it is. Freedom should be loved and very carefully guarded. It is the most precious property of life, a blessing that should not be taken for granted. On this wintry morning, I was endowed with this marvelous gift again and I lovingly cuddled it in my heart and every fiber of my being.

A knapsack over the shoulder loaded with cigarettes, coffee, chocolate, and all those items rare in post-war Germany, I went to the railroad station and arrived an hour later in Munich. Oh, Munich, what have they done to you? My beloved hometown loomed like a ghost city. Ruins, only ruins, where my eyes turned to. I tried to locate a telephone booth and finally found one burned and twisted. My train to Untersteinach left in the late afternoon. At 9 p.m. I was there. A dark and cold night embraced me. The stars sparkled in eternal beauty, messengers of hope and mirth. For 2 hours I pawed through the snow and up to Tannenwirtshaus, where Anny presently lived with her father. I was alone on the road. My mind, filled with immeasurable joy, ran ahead to my dear ones and I saw them in my fancy as they were 3 years ago, Millions could no more taste the great happiness of returning home. Oh, God, I had been spared to enjoy this moment beyond comprehension. There was the last hill. A dim light shone from the windows as I approached the house. With heavy steps, I walked up the staircase and opened the door. Moock stared at me in disbelief. Crying loudly, she flew into my arms. I was home. Really home. The war ghost, having haunted us for so long, finally left and vanished.