My life began under ugly circumstances. I was born out of wedlock. Today being born illegitimately is not an unusual event. Prior to World War I, however, a girl with a child out of wedlock was looked upon with contempt, at least in Germany. It was a faux pas, alright, but I owe my life to my dear mother’s mistake and this is sufficient excuse. To understand the circumstances, let me unfold briefly the story of my mother’s family, the Riederers.

My grandfather Alfons Riederer was apparently bright but had an aggressive and unstable character. To marry my grandmother, he more or less abducted her. This is readily understandable. The Spechts, my grandmother’s clan, lived in Schwaben County whose population is known as utterly conservative and thrifty. They, of course, had no sympathy for my grandfather’s lavish lifestyle. As far as I know, he nevertheless made his way and held the reputable position of a state official with the railroad department in Neumarkt, 25 miles south of Nuernberg in southern Germany where the family had settled. He died 39 years old, in 1891, leaving behind a wife with five small children and considerable gambling debts. In contrast to him, my grandmother, quite in line with her heritage and upbringing, was a sturdy person, hard, unbending, and determined. She had to be in order to survive and raise the children.

Karl, the firstborn, was his father’s image. As a young man, he roamed through the countryside like a gypsy, sometimes working, more often begging. When lost and in despair, he returned to his mother who again and again provided him with new clothes and sufficient money he afterward spent freely in no time. When he finally matured and his wild instincts calmed down somewhat, he married and moved to Czechoslovakia. Later he divorced his wife and married a second time. My grandmother disapproved of it and refused to see him and his new spouse in her typical manner. “I know only one wife of yours,” she wrote him, “your first one.” Karl’s son came in 1933 to Munich as a refugee sought after by the Czech police for his illegal political activities. During World War II he was killed in Russia.

Minna, the second child, was, according to my mother’s recollection, an outstanding beauty with shining black hair and scintillating blue eyes. The unique appearance obviously got her in trouble, and she committed suicide.

This tragedy had a profound impact on the family and in particular upon Maria who joined at 17 the order of the Poor School sisters. She was the good angel of the family, and I loved her very much. In her later years she became Mother Superior in her order and high in the eighties she died in 1977 in Wuerzburg.

Centa, the youngest, stayed in Neumarkt and married the heir of a wealthy merchant’s family. As a boy and student, I often spent my vacation with her making the 100 miles from Munich to Neumarkt on my bike. Her husband kept himself busy with all kinds of unprofitable hobbies and shied away from real work. He had no sense at all for monetary matters. During the great inflation after World War, I when the German currency rose to one trillion marks compared to one dollar, he sold all his items for worthless paper money. Hardly anyone attended their department store which slowly filled with dust. How my aunt Centa managed to provide food and other daily necessities for her family of 5 always puzzled me. Nevertheless, she was and remained a gay person to the ripe age of 90.

“Unsuspecting, he even agreed to give me the name Richard, which my mother apparently had proposed after her great lover.”

Anny, my mother, had apparently received a good education. She was efficient in typing and shorthand, qualities which enabled her to find pretty good jobs mostly with lawyers. Very young she was pushed into the world and became independent. Like every normal young girl, she had a great longing for love, marriage, and a family. Her two lovers, however, as far as I know, would or could not provide that. Mr. Richard Pollack, one of them, a lawyer, only abused her. After my mother’s death, I found his love letters which read like pornography. My mother was sexually so much his subject that she could not even bring herself to destroy these compromising letters after the breakup. I was 5 or 6 years old when Pollack married another woman socially more fitting for his academic career than my poor mother. He really dealt her a terrible blow. For hours she wept and cried aloud jolted by vehement convulsions while I tried to console her unaware of the circumstances.

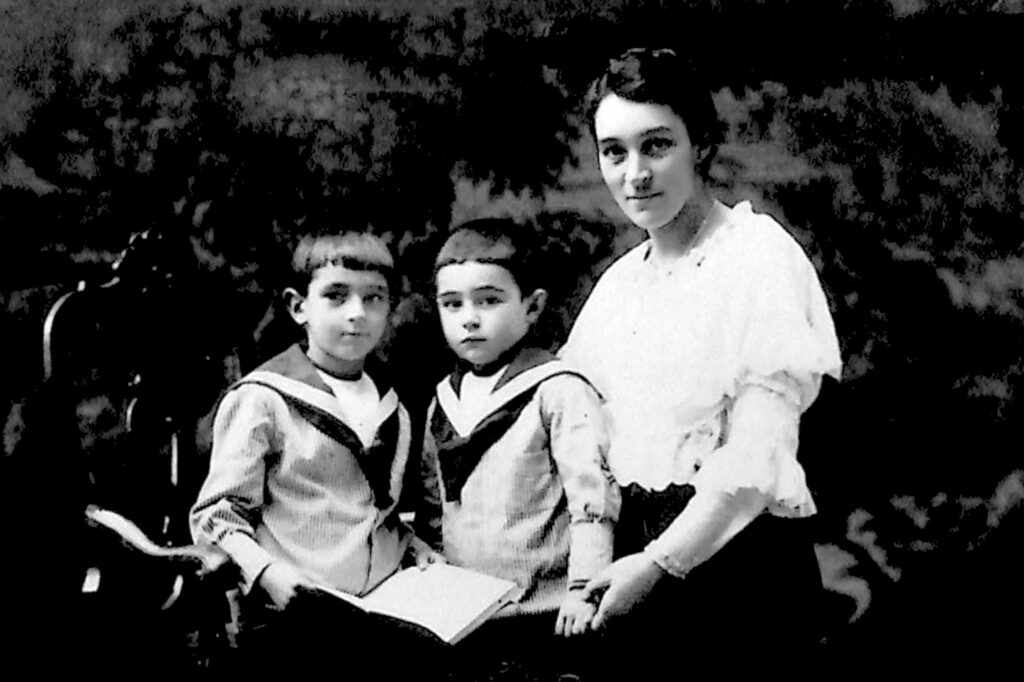

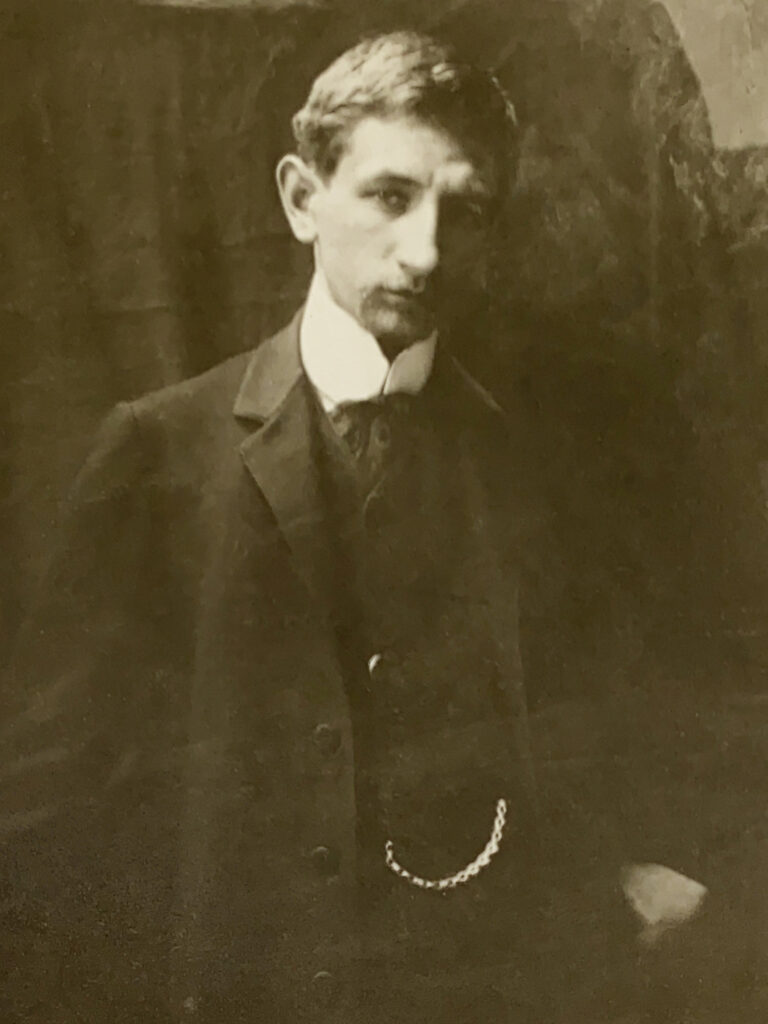

There was another man playing a role in my mother’s life either before Pollack or at the same time, Anton Rausch, a young art student, whose financial status ruled out marriage. He lived on a tight budget and was very much absorbed by his studies aiming at an academic degree. Anyway, during these turbulent times I came into the world, hardly expected with joy and unwanted. Officially, I was recorded on 19th November 1908 as the son of Mr. A. Rausch. Unsuspecting, he even agreed to give me the name Richard, which my mother apparently had proposed after her great lover. Eleven years later returning from the war he moved in with my mother and married her. Ironically, my brother Rudi and I led the couple to the altar I still remember very well the wedding dinner, which due to the food rationing was not very opulent; but the dessert called Virgins Kiss was so outstandingly delicious, that I never forgot it. With the advancing years, I observed that my mother was seemingly never quite sure which of her friends had really fathered me. One day I asked her frankly: “Who is my father?” She looked at me with an expression of distaste on her face and turned away without giving me an answer. That was disturbing and to some degree aggravated my affiliation with my father who felt rejected. After my mother’s death, I went to Fuerstenfeldbruck, a small town near Munich, rang the bell at Mr. Pollack’s home, and introduced myself. He was not at all delighted to see me and acted cool. This man was a stranger to me. I could not find any similarities between us nor was there any affection for him on my side. The interview at least made that point very clear. Slowly I came to recognize Mr. Rausch as my father not only by the official record but more so by blood, a view which was subsequently confirmed without doubt by my own son Felix who developed the unique features and complexion of the Rausches. In retrospect, I have only the highest appreciation for the courage and good nature of this man who accepted me and my brother Rudi as his children. He adopted us after the marriage and gave us his name. This is the more surprising since Rudi was registered as the son of Mr. Manasse, a Jewish commodity dealer from Erding, a farmer’s town in the neighborhood of Munich. Mr. Manasse paid alimony for Rudi and came to visit us once in a while. At one of these occasions, I asked him innocently: “Mr. Manasse, are you a Jew?” My mother felt very much embarrassed and furiously reprimanded me. Mr. Manasse was hurt and stayed away.

Returning to my Riederer grandmother, I would best describe her as a tall woman with a sharp nose and starry eyes. As often as I came to Neumarkt, I seldom missed entering her miniature house which she shared with another widow. In her presence, however, I never could quite warm up. She always behaved reserved and I assume she never forgave me that I was conceived with passion and without a priestly blessing. For the last twenty years of her life she was stricken by arthritis and spent most of her time in bed, but alert to the last minute. She died at 87 years old during World War II.

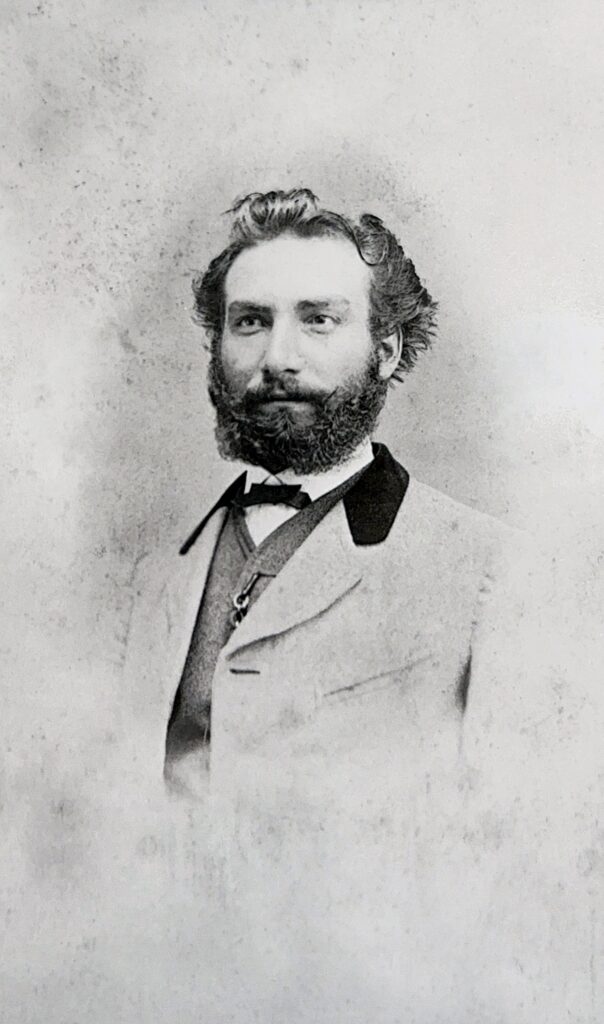

The life stories of the Rausch branch are for the most part shrouded in darkness. Both my grandparents had already passed away when I became old enough to show some interest in the family’s history. Therefore, I can only refer to the few details occasionally narrated by my father. Edward Rausch, my grandfather, was apparently an industrious, ambitious, hard-driving man who earned his meager livelihood as a painter and gilder in Fladungen located in the Rhoehn mountains, one of the most impoverished areas of Germany. Compared to the present standard of living which we enjoy, these people existed way below the poverty level. Their daily food consisted mostly of dumplings and salad from the vegetable garden. Meat was sparse and too expensive to be served except on Sundays. Motorization was not developed around the turn of the century. A craftsman had to make long trips on foot to reach his customers. The hardships were many. To endure the endless working hours from four o’clock in the morning to late in the night was one of the heaviest burdens. My grandfather was quite skillful in his crafts. The compelling necessities, however, forced him to accept mostly menial jobs. Only occasionally he had a chance to show his talent and paint a picture for the church. He suffered under these conditions and wished ardently that his son become a professional painter and conquer in the artistic world a place denied to him. For this purpose, he set aside a savings account from his meager income, designed to level the road for his son to the reputable Academy of Arts in Munich where he could study freely. Hardships and grief shortened his life. He was only 55 when he died in 1904.

My grandmother Rosalie bore 8 children. Seven of them died in infancy. To keep the last one she vowed to make a pilgrimage to the Shrine of the Fourteen Saints near Staffelstein, 50 km away, and skid up the hill on her knees praying from station to station of our Lord’s suffering. She kept the promise. Her heaven-storming faith was graciously rewarded. The eighth and only child remaining became my father. Like my other grandmother, she was afflicted by arthritis which confined her to a chair for many years. In that position my father painted her, the image of a mother who had overcome grief and sorrow and in deep meditative peace enjoyed already the bliss of eternity. In 1915 she gave back her soul, at 64 years old.