Fall 1948. The German Mark had been stabilized by a decree of the American Military Government. Every head of the population was entitled to receive DM 40- of the new money from the treasury. An excellent measure. Almost overnight all kinds of merchandise showed up on the counters, while the black market faded away. Business rode on the right track. Moock’s brother, who had taken over Opa’s business, made so much money within 5 months that he was able to lay DM 5000. – on the table, Moock’s hereditary share, a huge sum at that time. What to do with the money? Buy tools, start manufacturing something or take a job and acquire a home for me and my family? The decision was not easy and the first alternative exerted great attraction. Postwar Germany was in desperate need of consumer goods. The enormous destruction left by the war had created a vacuum promising ample opportunities for a new beginning in every field. Cash was the magic word. We had it, more than most people. However, my affiliations with business matters were rudimentary and, unfortunately, I lacked the keen sense to make money. Feeling clearly my shortcomings, I rather leaned toward the second alternative. I went to Munich and hunted for a job. The beginning was tough. 50% of all residential areas were deleted. Many thousands of Munich’s inhabitants slept on benches in concrete shelters. Finding just a place where one could stay through the night proved to be a hard task. My friend Luxi helped me out for the first weeks offering lodge and board. A terrific act of goodwill that I never forgot to appreciate fully. For the next 3 weeks, I ran up and down the city until I stumbled upon a position with the American Air Force at Neubiberg for a stipulated period of three months. Not in my wildest dreams could I imagine that this job would become the foundation my future life was to be built upon. From three months it extended to ten years and continued in the U.S.A. until I retired in 1973. The salary, very meager at the start, was sufficient to live with. Once this problem was solved, the Luxis grew seemingly tired of my intrusion, understandably so, and I stretched out my feelers for a substitute. One day I met incidentally Heinz Burghart, a good friend, and comrade from the days in Feldkirch. We talked about my plight and Heinz suggested spontaneously I move into his apartment. He always had a wide-open heart and this was true more so after he had passed through unbearable torments. Drafted by the Army in 1943 and sent to Russia he was wounded and in addition, spent years there as a prisoner of war. Deadly sick and afflicted by aggravated dropsy he was released to Munich and endured a 2 year-long painful ordeal in the hospital, while his unfaithful wife waited for his death. But Heinz recovered miraculously. Seeing no other way to get rid of him, she demanded a divorce. Good-natured and tired, Heinz agreed to every term. I mention this because his case was typical of the numberless tragedies arising in the aftermath of the war. Many women had remarried after their first husband had been officially declared dead. Suddenly he knocked on the door alive and in pitiful condition. Can anyone imagine the heartbreaking decisions imposed upon these women? Thus tragedies piled upon tragedies for years till the dust whirled up by the war had finally settled.

I had a place again to sleep in, at least temporarily, but time was running out. We needed our own home. After many attempts I found, a house located in a settlement named Wotansgarten, a subdivision of small vegetable gardens allotted by the city as a residential area. Luckily we managed to move our furniture down; no easy undertaking in those days, and in June 1949 the family was united and able to begin a normal life. By then I was 41. My best years had been wasted. I was not bitter about it, however, since I had learned a long time ago that every hardship as well as every joy plays a role and contributes to the unfolding of one’s personality. Our life for the last 10 years was comparable to a boat tossed and bounced through the rocky terrain of a gorge. Whirling over the last boulders we finally entered quiet flatlands. The days from now on vanished like drops from a leaky faucet clicking with the regularity of a metronome. There were little ups and downs, hardly noticeable. Slowly we expanded economically and emerged from the mud of poverty.

Three years passed without interference. Suddenly my job was in jeopardy. The dice had fallen. Accept a new assignment west of the Rhine River or get out. What choice did I have? None other than to agree reluctantly, which meant once again separation from my family for another 2 years. Spangdahlem was my destiny, a tiny forgotten village in the Eifel mountains. From one day to the other it gained significance with the news the American Air Force has decided to build an Air Base there. The workload burdening my shoulders was heavy, and the isolation was hard to take. In order to cope with it, I used my spare time to visit the principality of Luxemburg, the 2000-year-old city of Trier, founded by the Romans; and on sunny Sundays, I biked to the famous Eifel Mars, small but very deep lakes of volcanic origin embedded in a ring of cone-shaped hills. Surely, it was laborious to get over the steep heights of the Eifel, but rewarding also. I really began to love this quiet, forlorn region untouched by tourism.

As the leaves turned yellow and icy winds blew over the ridges I was transferred to Sembach, 15 km from Kaiserslautern, where soon the construction of a new air base started from scratch. Bavaria’s biggest building companies were employed to handle that mighty task within 2 years. Sembach was more to my liking. The neighborhood of a big city and the improved connection to my family in Munich made the situation more agreeable. In the meantime, I had been promoted to the position of a Field manager and Assistant to the American Project Engineer, who directed the entire job. Our staff had increased, to 20 people, barely sufficient to supervise the construction of 70 buildings, numerous roads, and utilities, a tremendous workload that often tied me down for 10 hours a day. Later on, the U.S. Project Engineer was transferred and I had to take full responsibility. This managerial job taught me many lessons. Constantly fighting the incapability’s and laziness of the subordinates as well as being in a position to defend their mistakes was slowly grinding me down and I felt no grief when this job ended 5 years later in 1958.

For more than one year I lived in a little community of Sembach, which had no attractions to offer other than the friendly relationship with Mr. Herzog and his family, the principal of the country school, and only one educated person among the farmers. Our love for music struck a harmonious chord between us and extended to a lifelong friendship. Nevertheless, my longing and never-satisfied thirst for cultural events became strong enough to consider a move to Kaiserslautern.

“Sembach, which had no attractions to offer other than the friendly relationship with Mr. Herzog and his family, the principal of the country school, and only one educated person among the farmers.”

Almost a decade after the end of WW 2, West Germany’s reconstruction program ran in high gear. The ruins gradually disappeared thanks to the massive U.S. aid pumped into many European countries including the former enemy. The recovery was pushed with utmost speed and the Germans in particular, work fanatics by nature, would not rest until the restoration was complete. New buildings shot from the ground like mushrooms and the American Military also hastened to provide a subdivision for its numerous employees. A few months before the completion, in the summer of 1954, Moock and Ekke joined me and we rented a farmhouse in Sembach. Sorry to say, but the house was infested with mice and very uncomfortable and we looked forward to the day we could finally move into our apartment. Felix stayed in a Catholic student home (Salesianum) in Munich according to his own wish. He wanted to be alone and independent, but the rigorous discipline of the institute soon changed his mind and gladly he joined us half a year later. A wonderful period of our life began. I had a highly-paid position. We resided in a spacious apartment and even could afford to buy a car. In the years to come, we traveled a lot, not only to discover the beauties of Germany. Our tours led us through France, Italy, and Austria and I hope these journeys left a lasting impression also in the memories of our boys.

At the end of 1957, my office was informed the job will run out within one year. I thought it very considerate to tell us the bad news so far in advance. That way everybody had ample opportunity to shop around. During those days we happened to have a visitor from the United States, Moock’s brother Fritz, who lived for 25 years in Connecticut. He suggested that we emigrate to America and offered to put down the required warranty (sponsorship). Starting a new life in a strange country needs a clear decision not easy to come by. After all, my 50th birthday was just around the corner. Fully aware, however, of the opportunity I did not want to miss, I filed the necessary papers. Facing such a daring and risky endeavor one might wonder what thoughts had beset my mind. Actually, I did not rationalize but listened almost exclusively to my inner voice, as many times before, which urged me to go and the desire grew the closer we drew to the date of departure. The American Personnel Office had other quite well-paying jobs available for me, including a position in Iran (Turkey), but I declined. My inner voice said “No,” and I obeyed fully aware of the immense difficulties laying ahead. So strong was my confidence that I prepared everything like being in a state of trance. All the warnings and well-meant suggestions of friends and relatives could not touch my innermost feelings.

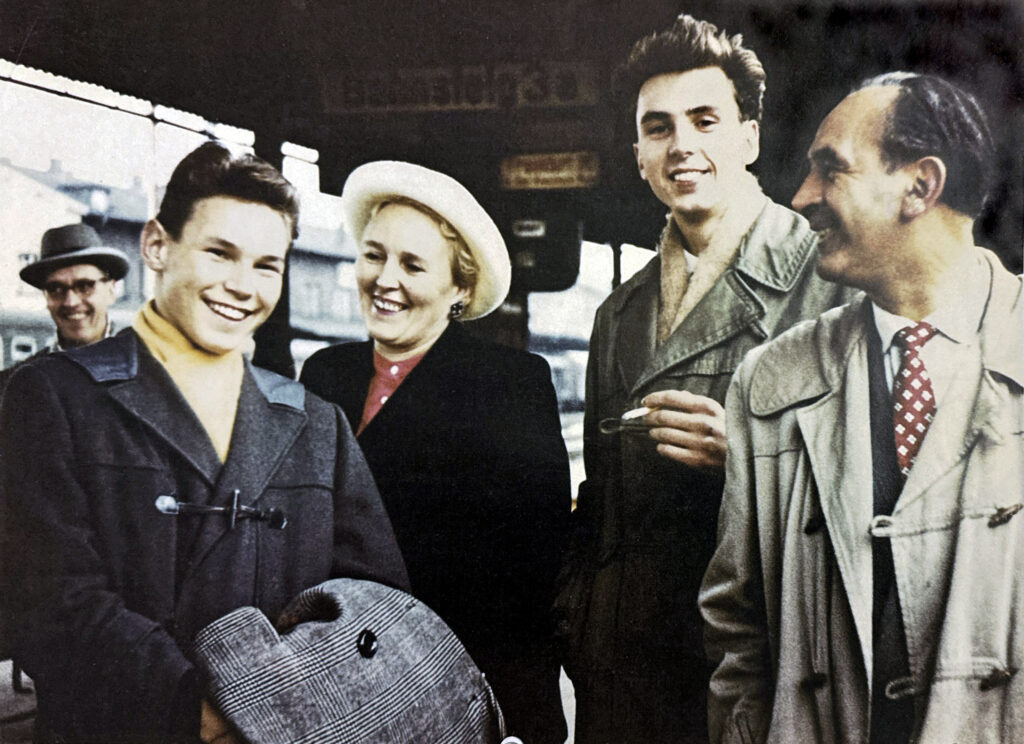

On Sunday, the first of November 1958, we departed. The sun smiled when we said farewell to our many friends who had assembled at the train station. Our hearts were tense, but I had no doubt we would master the future.