1933 was an ominous year hammered into the books of history with black letters. The political jumble of the previous years spilled to the surface a terrifying power that took over the fate of Germany and played the nation into the hands of Adolf Hitler. Who was this man with the many faces who had the potency to hold large masses spellbound with magic power? Years earlier I went to one of Hitler’s campaign rallies curious to hear and see this figure everybody was talking about. What I experienced was a rather interesting spectacle. Mr. Frick, a representative of Thueringen, opened the meeting with a lifeless and boring introduction. Then “He” stepped onto the stage. Ominous silence. Slowly and quietly dropped the first words from his lips increasingly growing to an angry growling and stepping up to an infuriating staccato. Shouting and roaring he pounded the ground with his foot in rage and wrathful indignation. Looking around I saw the feverish eyes of the crowd glued to this frenzied storm on the podium, while the big hall quivered with bursting energy. Like a master on his instrument, he played with these people’s emotions, pulling them through all phases from humor to anger to enthusiasm. It was due to this unique faculty that he was able to reach the godlike stature which enabled him to abuse the nation according to his whims, Behind his patriotic rhetoric lurked a ruthless craving for absolute domination. His often-mentioned goal to make history was only a veiled synonym for playing war and gambling with the lives and properties of people. Scrupulously he whipped his followers and they licked his hands. A truly Satanic figure with a demonic lust for hatred and destruction.

One afternoon Willi Gerstacker and I sat in a tea parlor chatting when suddenly the doors were flung open and Hitler stepped in king-like, surrounded by his bodyguards. He took his place and sipped his tea in silence staring into emptiness. 15 minutes later he got up and stalked to the door with stiff legs. I caught a close look of his face which reminded me of a biting rat. But his tightened cheeks and the stern glance in his eyes revealed a tremendous energy, a volcano ready to erupt every moment. Which words I ever choose to describe his character, will never suffice to express the strange mystique wrapped around this man who escaped all assassination attempts until his mission was fulfilled. Then and only then he eliminated himself. Yes, I believe he had a mission: to scourge the nations and drive them out of their shallowness and shameless adoration of materialism.

In March 1933 Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany by means of a legal, democratic process. A wave of enthusiasm surged through the country sweeping aside the warnings of a few. His dwarfs busied themselves with ant-like servility to fortify his throne, tossing innocent people out of their rightfully held positions and substituting them with loyal party members. The ignominious purge was total and certainly did not stop at the gates of Munich. It was a wonderful, sunny afternoon when the clean-up team began its job in Munich also. Just at that time, I happened to pay a visit to Miss Schrnagl, the major’s daughter. I knew her from our fraternity parties but never dared to approach, much less court her except for an occasional dance. She was a beautiful woman with dark, glowing eyes. Whatever reason she had to seek my company, I might just guess. Anyway, she took the initiative and invited me to her residence. We spent together a most delightful afternoon when unexpectedly her brother stormed into the room and announced the dire news: her father had been rudely deposed with brachial force. The pleasant atmosphere was instantly destroyed. The far-reaching implications for the whole family were obvious. What choice did I have in this ominous moment than to excuse myself and leave the house in distress, thus ending my first and last rendezvous with an exquisitely charming lady. From there on she refrained from the fraternity entertainments and I never saw her again.

“I had to rely upon my own musical instinct in finding my way through the jungle of modern music.”

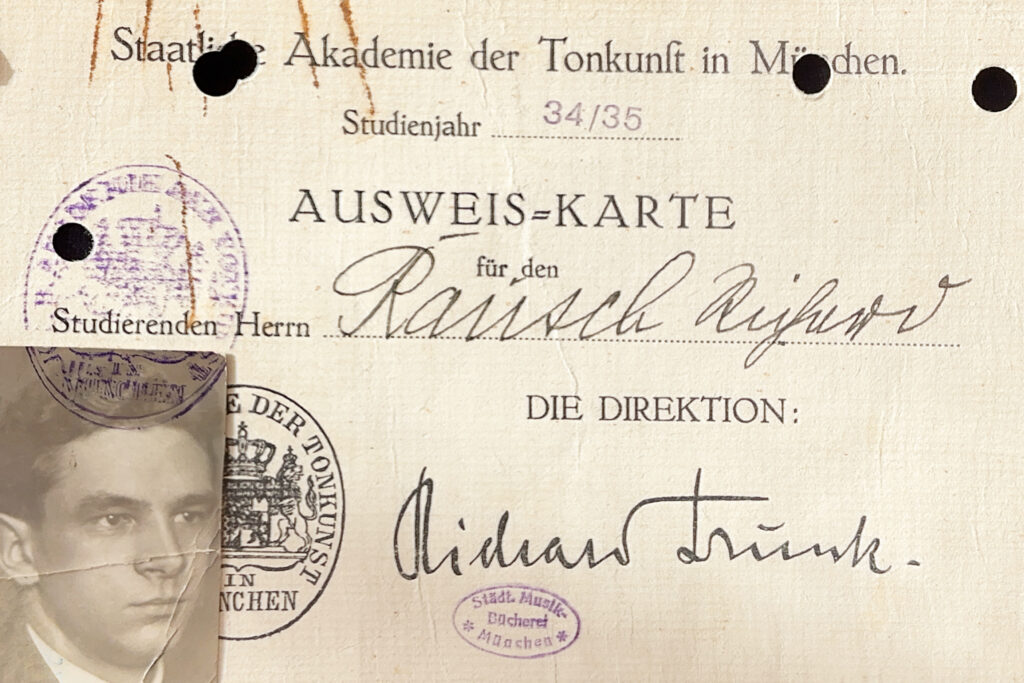

I myself lost also interest in fraternity activities, but for different reasons. The entrance examination to the Academy of Music was too important a battle to be lost. For a long time, it was my innermost goal to study at this famous and reputable institute which, I fancied, was indispensable for a professional musician in order to be accepted by the musical establishment. In spite of my incredible nervousness, I passed the examination and with untiring vigor, I threw myself into the task of discovering the hidden architecture of great music.

My teacher, Mr. Haas, a local celebrity, introduced us to the mysterious details of composing with meticulous exactness. Unfortunately, he was very conservative and never granted the students a glimpse beyond the acknowledged masterworks. He even avoided any discussion of modern music which apparently was strange and inaccessible to him. Of course, it was a necessity to become familiar with basic craftsmanship, but the future composer has the duty to broaden his view and include in the learning process contemporary achievements also.

Since I could not afford to take lessons from an accomplished composer of our time, I had to rely upon my own musical instinct in finding my way through the jungle of modern music which had invalidated the century-old rules and resorted to the discovery of unknown sound combinations. Fascinating as they are sometimes, the results, however, were all too often not new music, but rather ugly, cacophonies unappealing to the broad audience of music lovers. With growing concern, I observed the deep rift setting apart contemporary music from the familiar pattern. In vain I searched for continuity which in my opinion was an essential ingredient in the composing process. Recognizing that in fact there is no continuity, left me confused and unhappy. A real genius would have closed the rift, but I was not born as a musical genius and did not see anybody else accomplishing the impossible. Today, 50 years later, I view the problem somewhat differently, but the original analysis done in my early manhood still holds.

During the first semester of 1933, my hopes were still flying high. I worked so hard for months that my father felt some relaxation was due. Since the days were summerly warm, we decided to visit Aunt Centa in Neumarkt. On the first two days, we extended our sightseeing excursions to the neighborhood; on the third day I decided to stay at home. It was the 29th of July 1933, an unforgettable date. A strong yearning to play on the piano had grabbed me and I sat down to lure out [of] the old, defensive instrument the eternal music of Beethoven’s 4th piano concerto. The Adagio, a piece of infinite sadness and utter despair, held me spellbound when suddenly the disconcerting sound of the telephone cut my dreams. My brother Rudi was on the “Mother is very sick,” he said, “Come home at once.” I could not understand “It is so nice here,” I replied. “Is she really so sick?” “No delay,” he admonished. “Return immediately.” Crestfallen and disturbed I ran up to my room. A few minutes later Mr. Koller, Centa’s subtenant and a good friend of ours, entered. “Richard,” he urged me with a hoarse voice, “sit down.” And after a moment of silence, “Your mother is dead.” I stared at him in disbelief. My mother dead? She was laughing and happy when we left 3 days ago. Still, I was unable to comprehend the awesome fact completely until the true and horrible meaning fell upon me with a staggering weight, pressing a stream of tears from my eyes. In vain I tried to behold her beloved face, to collect myself and come to grips with the smashing fact. But there was no time to be wasted. We packed immediately and Mr. Koller drove us back to Munich. What an endless road it was. My heart called impetuously on my mother. Why did you leave us? What happened? How does she look? Finally, we arrived. I flew up the staircase and there she was, laying in the coffin, white-faced, with a sphinx-like smile around her lips. Flooded with tears I sank into deep darkness mourning in unbearable pain and crying aloud and unrestrained until Rudi tapped me on the shoulder and pulled me back to reality. “How sweet she smiles,” I whispered and could not turn my eyes from her lovely face which soon would disappear forever.

Late in the afternoon, they carried her away. A massive stroke had ended her life. It happens every day many times, and we read it in the newspaper without being touched. Only the personal confrontation with this irreversible fact is a crushing experience. Out of the abysmal chasm between life and death reaches an icy hand pointing to the dark land where we all have to go one day. The night following that day brought no relief. Dreamlike croaking shadows whirled around me and threw me into unfathomable darkness out of which my mother emerged in a clear and real form. She stood next to me, quiet and seemingly depressed, ironing shirts, the last job she had performed on earth. The trauma haunted me for many months and during the years to come, she appeared once in a while in my dreams, always sad and silent. The last time I saw her many years later she walked toward me hand in hand with my father smiling and frolicking. “How come you are living?” I uttered in astonishment and simultaneously an immeasurable joy welled up from the depth of my heart pulsating through my entire being like a powerful electric current. Was it a dream or a divine message? I don’t know. Maybe my parents wished to assure me of their final peace.

The weeks and months following the funeral were drab. Marie, Cento’s daughter, stayed with us and tried to fill the gap in a suddenly womanless household. Her decision to remain did not entirely spring from charitable feelings. Marie approached the age of thirty and had not yet found a husband. The opportunities offered by a capital city like Munich, she figured, could very well help to eliminate the deficiency. In spite of her earnest efforts, however, a year passed by without success. Regretfully and beaten she decided to return home to her mother leaving us behind with the dilemma to find somebody who was willing to care for three helpless men.

An advertisement in the local newspaper lured a young woman to our house. She was black-haired and tight-lipped, a former nun who had left the convent to quench her burning earthbound thirst with a good dip into the boiling waters of fleshly passion. Abused and kicked out by her brutal-faced lover, she found herself quickly trapped in the mire of everyday life and searching for a shelter where she could stay with Traudi, her 2-year-old daughter. Traudi was a sweet little girl and brought lots of sunshine into our otherwise joyless home contrary to her mother’s unbearable restlessness.

The general economic situation in Germany had visibly improved since Hitler had taken over the government, but the warm precipitation of wealth felt throughout the country did not wet our garden. My father’s purse was still empty most of the time and the burden to carry a household of six under these conditions seemed to go way beyond his capabilities. His health began to fail. Sudden spells of a total blackout occurred more often. Then he fell to the ground like a rock under heavy convulsions and several times he injured himself considerably. Returning to consciousness after a little while he could not remember anything. Since he refused to attend a doctor, nobody was very much concerned, although it frightened me every time I experienced an attack. The strain my father was exposed to must have been unbearable. It was not only the chronic lack of money, his oldest son, already 27 years of age, had still no income and chased a dubious goal without a future; Rudi had dropped out of school but was smart enough to learn the banking business. He was the only one besides my father who contributed a few pennies to the household. Toni, deprived since his early years of motherly love and most of the time pushed around by all of us, flunked school one year after another. The domestic atmosphere was so bleak and depressing that the ill effects were felt by every one of us. I myself suffered from exhaustion which more than once carried me to the brink of a nervous breakdown. Something had to be done. What alternative did I have? Cut short my studies and look for a job? To bring clarity to my confused head, I opted for a one-week retreat to the loneliness of the mountains. Two months before the final examination I packed my bicycle and took off to Bad Toelz where I left it with friends.

I hiked up the long winding roads to the Benedicktenwand, 6000 feet high and down on the other side, up and down, mountain after mountain. What a joy it was to perceive the grandiose panorama of the towering Alps. The days endowed with golden sunshine were warm and cozy, the air strong, but gentle. I drank the spicy mountain waters and ate with the hillbillies for a few pennies. The nights I spent in open barns and found great delight to listen to the solemn quietness of mother nature. My body became vivified and my mind susceptible to the magnificent design of the world. What a wonderful feeling it is to be close to the breath of the Universe and tune in joyfully to the music of the spheres.

Back in Munich, the old misery crawled over me like a big snake and my instant reaction was to flee. The position of a prefect offered in Ingolstadt, 100 km north of Munich, came in handy just in time. I applied and was accepted. The director and his assistant were young, friendly priests; the boys, were students from the neighboring countryside. Supervising the students was the main duty besides conducting the boys’ choir and tutoring them occasionally. The seminary was in possession of a grand piano with excellent sound and, of course, I used it in my spare time as often as possible to maintain my laboriously acquired virtuosity. The director often praised my pianistic abilities and rated them higher than those of the well-known local piano teacher who stalked around the seminar like the king of music. The easy-going, pleasant life gave me even the courage to compose a symphony that in my judgment was good enough to be performed in public. Why, for God’s sake, it never dawned on me how easily I could turn my musical capabilities into hard cash still remains a mystery to this date. I know only that my sense of practicality was dormant or, to use a more accurate term, paralyzed. Instead, I spent my time flying high up in the clouds, and thus I missed the golden opportunity to establish a musical career at the given level. More important to me, obviously, was to grapple with the rising power of the Third Reich and in particular with the philosophical aspects revolving around the Germanic Superrace, the core of Racism. More than once I clashed with the radicals among the students who went so far as to threaten me because of my black hair and dark complexion. Fortunately, I was able to prove my Aryan heritage and they stopped short of reporting me to higher authorities. Regretfully, I have to admit that I adapted some of the new ideas although they bothered my consciousness and caused increasing mental vomiting. After 14 months of lingering along this way, I quit the job and returned to Munich, sad, confused, and shattered. I had wasted precious time and talent. I had also wasted the sweat and sacrifices of almost a decade. Now I had to pass through the lowest valley of my life. Oh, how bitter it was to turn away from all the cherished dreams and walk toward the icy air of reality unaided by the strength of an inner vision. Goodbye sweet and ever-consoling world of music. The time had come to extinguish the fire and depart from the exciting realms of the past. Great accomplishments I had in mind. Weighed and found too light, however, I was thrown into the pot of the undistinguished. Humiliation, indeed, is one of the hardest punishments.